Fostering a college-going culture

By: Carley Milligan, Editor-in-Chief

Towson University junior Omnia Shedid received a text from a 12th-grader at Dulaney High School in Baltimore County in early September. It was one of the students she was mentoring at her alma mater.

Hey, what’s my maiden name?

Shedid looked at the text in disbelief, and as more questions about income, FAFSA and the college application process flooded her inbox, she realized that her mentee was most likely not the only high school senior with similar questions.

“I can think back to when I was going into college,” Shedid said. “My mom speaks little English, my sister was at UMBC. I had no help with the college application.”

As a political science and international studies major and a member of the leadership of the Student Government Association Senate, Shedid assembled a team of senators to create the Higher Education Initiative (HEI) and address the problem.

The initiative focuses on helping students in Baltimore City and County public schools prepare for life after high school with information about applying to four-year colleges, community colleges, trade and vocational schools and various forms of financial aid.

“I feel like all high schools are kind of struggling with the Baltimore uprisings happening, and all this stuff going on in Baltimore,” Shedid said. “There was just this tension and I thought, how do we expect students and high school juniors and seniors to be concentrating on colleges with all of this going on around them?”

Reinvesting and reengaging in urban schools is an objective of Towson’s College of Education, according to Dean of the College Laurie Mullen, who was appointed to the position over the summer.

The college, which boasts 150 years as a school for educators, is Maryland’s oldest and largest producer of teachers. Mullen and Shedid both said that the college is in a unique position to support Baltimore’s urban schools.

“I think that having students come into an education program, say at Towson University, and get that education and then hopefully take it back to their home because they see how much they struggled and how much they have learned as a result of that struggle … that is very important,” Shedid said. “And I think it is possible.”

The HEI visited their first school, Franklin High School in Baltimore County, Oct. 16. Shedid and five other senators spoke to an auditorium of juniors and seniors about topics like being a first generation college student, financial aid, the college application process, college life, the option of vocational and technical schools, and diversity in college.

“The first ten minutes of the presentation you could tell they were rowdy, they weren’t really paying attention,” Shedid said. “But things got personal with each speaker and we each shared our story and instantly the students were just like, ‘Oh my god we need to listen to this.’ You could just see in their faces.”

The experience of being able to speak to each student directly, and get them thinking about their life after high school, was what Shedid said made the initiative a success.

“[The students] were engaged, they were very, very responsive, very inquisitive,” she said. “It was question after question and then afterwards they had to extend our time because we just couldn’t stop talking.”

Franklin High School, located in Reisterstown, is ranked 123rd of the 228 Maryland public high schools, according to schooldigger.com.

The second school HEI plans to visit, Patterson High School in Baltimore City, is ranked 212th by the same website and sits fewer than 10 miles from campus.

In the last four years, students from Baltimore City public schools have applied to TU with cumulative weighted GPAs ranging anywhere from a .98 to a 4.5.

The academic disparity between individual students in both Baltimore County and City schools is vast, and according to Shedid, standardized guidance in public schools has its faults, similar to standardized testing.

“When I visited Patterson they talked a lot about the African refugee, and Iraqi and Syrian population, and those students are not going to connect with your average guidance counselor,” Shedid said. “Schools tend to have a standardized guidance plan for the college process and life after high school, and they have to understand that what they are using, that plan, is not going to fit every student.”

HEI has yielded positive feedback from city and county high schools, in as far as encouraging students to think about their plans beyond high school.

However, according to Towson Director of University Admissions Dave Fedorchak, ensuring that a student’s GPA and test scores are high enough to be admitted to the school of their choice must come first.

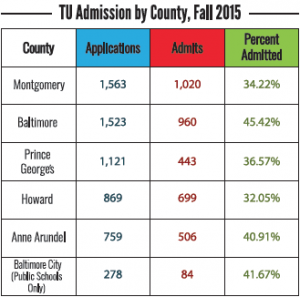

This fall, only 30 percent of 278 Baltimore City public schools applicants were admitted to TU. Fedorchak estimated that each year, only about 75 percent of public schools in the city will have any students who apply to TU.

This table represents the total number of applicants, admits and the percent admitted who enrolled from six local counties.

“It’s not just a test score that means something or a GPA, but it’s how do you put all of that together to provide yourself with opportunities,” Fedorchak said. “Many of the times when those seniors get [to graduation] their opportunities are zero, or very very few, and I say ‘well you have to do this.’ And I always tell the young kids, wouldn’t you rather have options rather than have someone tell you what to do?”

Targeting students from a younger age is a tactic that Shedid plans to incorporate into her work at Patterson.

Fedorchak has also begun focusing on young students, through a partnership with the Center for Student Diversity (CSD) and the Maryland D.C. Campus Compact AmeriCorps VISTA service.

Through the program, TU works with ninth grade students at Vivian T. Thomas Medical Arts Academy in Baltimore City, to promote college readiness and a college-going culture in the community. Next week, they plan to expand the program to Reginald F. Lewis High School, also located in the city.

Providing young students with information about what colleges require of them academically, Fedorchak said, will hopefully increase the number of students admissible to universities like TU. He has also started bringing younger students, particularly those between seventh and 10th grade, to tour Towson’s campus as one method of engaging them in the idea of the college lifestyle.

Shedid hopes to do the same with the freshman and sophomores at Patterson in the coming months.

“In the city specifically, talking to the younger kids is the main way I think we can change the college going culture within the city,” Fedorchak said. “If we get to them earlier, we can help them.”

Fedorchak also said that finding ways to speak to young students about college more frequently would help.

“The one time thing doesn’t work, it has to be a message that is repeated over and over again,” he said.

The creation of “success programs” over “access programs,” Fedorchak said, is also an important part of increasing academic success.

An access program like the Top Ten Percent Program, which offers Baltimore City or County public school students ranked in the top 10 percentile of their class the opportunity to apply to TU under specific admissions criteria slightly lower than that of the general admission population, is not useful unless those students are able to succeed once enrolled.

Federchak also points to success programs like Towson’s SAGE (Students Achieve Goals through Education) mentorship program, which focuses on academic success, cultural and racial communities, and personal and professional development.

“The major intent of SAGE is to connect new students with a peer mentor who will help them to make the transition from high school to college,” Director of Student Success Programs in the CSD, Raft Woodus, said.

Fedorchak believes that college is not necessarily the right move for every student, and that the way a counselor or educator goes about providing guidance to urban high school students about how they can be successful after graduation is important.

“I think that once they know that you care, that you are there to help and that you can educate them on what they need to do, that’s I think when the barriers kind of come down and they see you as the same type of person, and an equal, not ‘who is this person who has no idea what I am dealing with,’” he said.

Fedorchak, who is a first generation student from a small town in Pennsylvania, where his parents worked in factories, said that in some ways, his upbringing has helped him to connect to urban and low-income students and families. However, he feels the approach of the individuals seeking to help is more important than their personal experience.

“Just because you came from a background that may be different from them, you have to figure out what makes them tick, what types of things they have experienced, and I think being there and seeing things and going through that, then helps you to relate to the students,” he said. “I would never tell a student that I know exactly what you are going through, but I say ‘okay help me learn about that, and then what can we do to help you get where you want to go.’”

Shedid, whose family emigrated from Egypt when she was five years old, said that she believes many individuals return to work in urban and low-income areas in order to give back to the community that they came from.

“I struggled with it, a lot of my friends struggled with it, and it’s one of those things where you have to take it and you have to make a promise to yourself to pass it on, you are passing on that torch of knowledge to them,” she said.

From her work with HEI, Shedid said she has learned there is a need for educators and counselors in schools who can better connect to the population of students they are serving. For example, having more Spanish-speaking, non-white teachers for English Language Learner (ELL) students would be beneficial because of the connection that sharing a common, native language can produce.

In response to that nationwide concern, Towson’s Department of Elementary Education is forming a cohort of elementary education teachers with an emphasis on ELL this spring. Additionally, in order to attract a greater number of minority teachers, Mullen has started to create a new scholarship for minority students in the College of Education.

Researchers have found that the demographics of Kindergarten-12th grade students are changing, Mullen said, and that what were previously considered to be minority students are now the majority in contrast to the constant demographic of primarily middle class, white female educators.

“We do know that minority students, students of color, perform better in schools when they have teachers of their own ethnicity, and it is very important that we respond to that,” Mullen said. “Kids need to see role models and we want to make sure that teachers who may have similar experiences as the kids that they serve are working with them, and perhaps can relate to students in different ways.”

Working with the Urban Teacher Center, sending more student teachers to Professional Development Schools in the city, and providing incentives and early contracts to recruit young teachers in the city, are a few ways Mullen said TU can harness the passions of students who want to teach in urban areas.

“The more educated a community is, the better off a community is,” Fedorchak said. “Figuring out how to kind of break that cycle that some of the students have been in, and the lack of exposure that they have had to certain things, that will get them to go back and talk to those people who are still there.”