Mexican-American poet tells tales from the border

By: Ashley de Sampaio Ferraz, Staff Writer

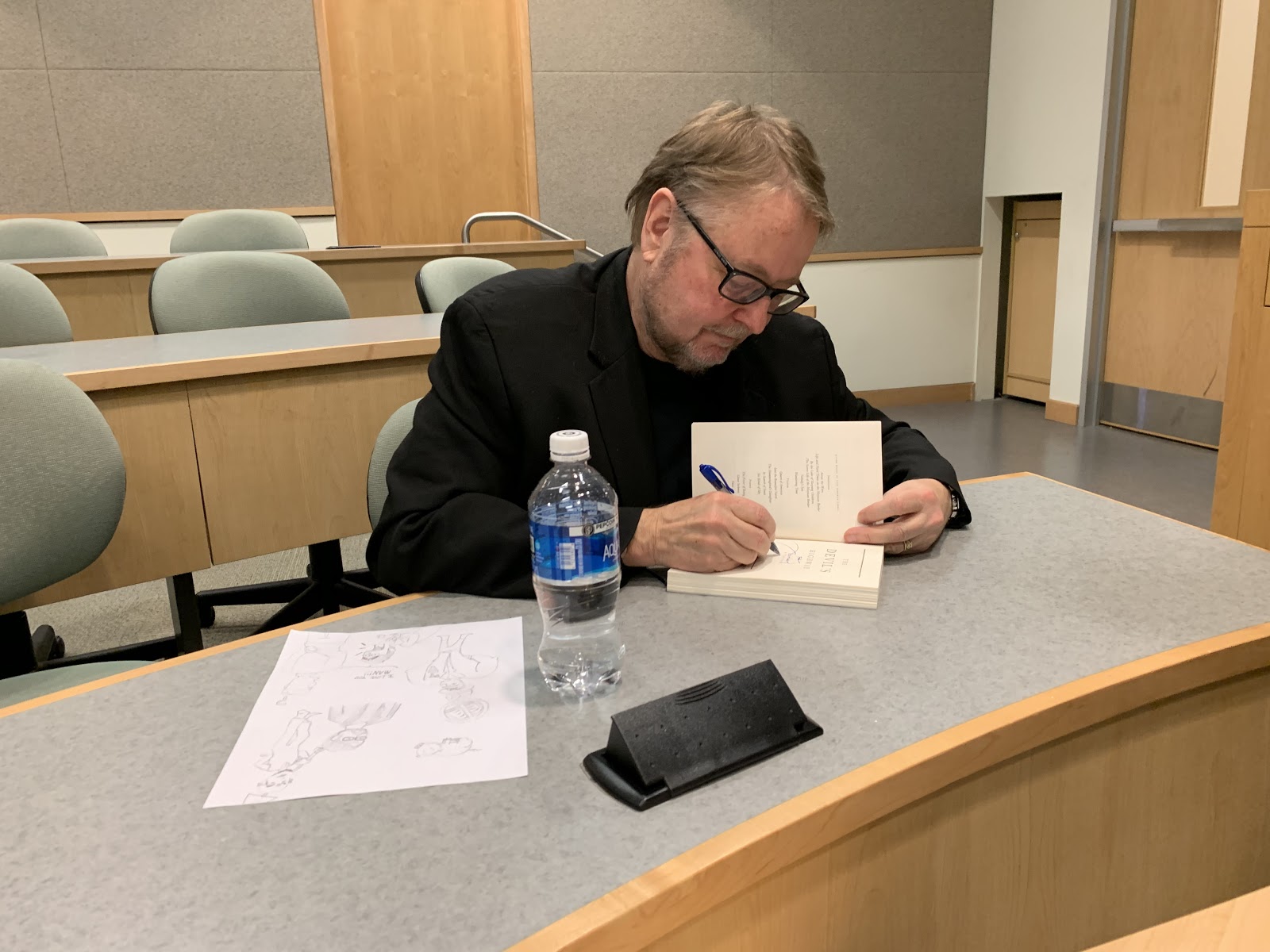

Photo by Ashley de Sampaio Ferraz/ The Towerlight

Luis Alberto Urrea, a distinguished Mexican-American poet, said that it is important to witness the unfamiliar, during a talk at Towson University Wednesday.

“We need to try to bear witness in some way that isn’t always pointing a raging finger,” Urrea said.

The attentive crowd, a mix of both students and members of the public, filled every seat as Urrea shared stories of his past adventures and experiences writing about the border and the impoverished people of Mexico.

“I remember one of the critics said that I wrote the funniest tragedies in the world,” Urrea said. “And I thought, no, not really, it’s just that people are funny. If you were in my writing workshops, you’d know all of my weird commandments, but one of them is: laughter is the virus that infects us with humanity.”

Urrea has written 17 books, and was a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize with his book “The Devil’s Highway: A True Story” and is a member of the Latino Literature Hall of Fame. He said he first began writing about Mexican culture after going on a mission trip to Tijuana as a recent college graduate.

“In those days, we were one of the first groups doing stuff, working in a Tijuana municipal garbage dump with the garbage pickers, recently arrived migrants, indigious people working in prisons, working in orphanages and various barrios,” Urrea said.

Urrea studied both theatre and writing in college and said that he originally wanted to use his talents to be rich and famous. Then, during his senior year of college, his father passed away suddenly while on a trip to their hometown in Mexico. The suspicious circumstances surrounding his father’s death drove Urrea to want to help others.

“I just had to give back after what happened to my dad,” Urrea said.

After arriving in Tijuana, Urrea worked as a translator for his group, and said that, as a result of his position, he had to witness a lot of gruesome situations.

“Translators, if you have the gift of speaking it, you have the responsibility of listening to it,” Urrea said. “People need to tell somebody whatever they’re going through, and that was me.”

These days, Urrea shares what he’s learned throughout his experiences to audiences across the United States.

Freshman Kelly Murph said that she found Urrea inspirational because of his dedication to telling the stories that most may overlook or think aren’t significant enough to share with the world.

“I guess that he found every side of every person’s story important to the larger narrative,” Murph said.

Urrea’s commitment to telling everyone’s story doesn’t only apply to impoverished Mexicans. During the talk, he also shared about his experience speaking to a U.S. Border Patrol agent when he was writing “The Devil’s Highway,” a book about the Yuma 14, an event where fourteen illegal immigrants died while being smuggled across the desert in the United States.

“I was really big on bearing witness on my people, who I felt were my people, but I had gone in there with prejudice,” Urrea said. “I was going to trash the border patrol, I was going to write a book about how evil they all were, because that’s what I thought.”

Urrea said his plans changed once he began to connect with the agent.

“The first thing [the agent] said was, ‘if my wife was starving, I’d enter any nation on earth to feed her,’” Urrea said.

Urrea shared that as he and the agent continued to speak, he started to understand the struggles border patrol agents have to go through in their daily lives. Urrea believes that being angry at each other is not a very good way for our country to solve its problems, and instead, people need to listen to each other again.

“In a lot of ways, love is more powerful, in every way, than rage,” Urrea said. “The hauntings in those men, even though I often think badly of them, are real.”

Kaitlin Marks, a student at Towson University, said that she agrees with Urrea and believes everyone could use a little more understanding, especially when it comes to border patrol issues today.

“I think that we all need more empathy,” Marks said. “And I think that if we approached the situation and used the context of where people are coming from it might be a little easier to understand why they want to come here.”

For now, Urrea just wants to spread a message of unity and understanding among his people, both Mexican and American. He believes the best way to do this is by close communication.

“I think we’re in the middle of a tumult, that is going to be hard to define yet,” Urrea said. “I’m seeing a lot of people writing their own stories. If we can listen to the dreamers, if we can listen to the undocumented as well, and try to understand what it is; I think we understand what we think their story is, but we don’t often sit with them and ask, ‘what is your story?’”